Asian American Women and Cervical Cancer

According to the National Asian Women’s Health Organization, Asian-American and Pacific Islander women have the lowest cervical cancer screening tests in the country and have a greater risk of developing cervical cancer than any other race.

“I have never gotten a Pap screening, but I know I should be getting one. I think a lot of Asian-American women don’t get tested because they don’t think it applies to them,” Pascale Ngo, 21, a Chinese-American said.

The older generation of Asian families has made a profound influence on the lifestyle and expectations that Asian women should live up to

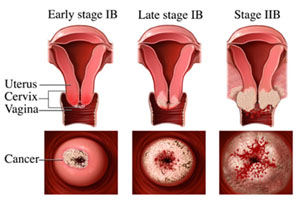

A Pap test, most commonly referred to as a Pap smear, screens for changes in the cells of a woman’s cervix. The Pap test can identify any abnormalities, including yeast infections, unhealthy cells and cervical cancer. The National Women’s Health Information Center, a part of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, recommends that women age 21 should get a routine Pap test every six months, but women who are as young as 18 and are sexually active should also be tested regularly. Cervical cancer does not discriminate against age, so it is necessary that older women, too, get tested yearly, if not more often. For instance, women who are 30 years-old and have had three normal Pap tests for three years in a row should ask they gynecologist about spreading their Pap tests apart two to three years.

While Asian-American and Pacific Islander women are among the least likely to get recommended Pap tests, many Asian-American and Pacific Islander women say that they are almost always offered cervical screening tests but are too ashamed or afraid to take one.

“I am an Asian female who’s too ashamed to even go to the gynecologist. If my mom found out, she would get suspicious. That’s just how the older generation portrays things, and I think that in itself impacts some of our decisions, not just about STDs. On the other hand, just because you get cervical cancer from an STD, it doesn’t necessarily mean that you’re promiscuous,” Jamie Fabros, 21, a Filipino-American said.

The older generation of Asian families has made a profound influence on the lifestyle and expectations that Asian women should live up to, and as a result, some misperceptions and stereotypes persist from these expectations. Cathy Vu, a 22-year old Vietnamese-American marketing student at Pace University in New York, says that the most irrelevant factors like ethnicity and a general routine check-up to the gynecologist can imply many things about a woman.

Vu said, “For one thing, I know in some Asian cultures that if you’re dating a girl who is not of the same ethnicity, she’s already seen as an outsider. My Vietnamese friend was dating a Korean guy, and he broke up with her because she wasn’t Korean. Moreover, in some Asian cultures like Japanese and Korean, if a woman visits the gynecologist or even a doctor, it implies that she may be unhealthy and therefore, not fit to be someone’s wife.”

Despite her family’s conservative values and misperceptions about Asian women, Vu continues to make yearly visits to her gynecologist and has considered taking the vaccine Gardasil to reduce her chances of getting cervical cancer.

However, some Asian-Americans feel otherwise. Dr. Yi-Shin Kuo, a gynecologic oncologist at the Albert Einstein College of Medicine/Montfiore Medical Center who writes about cervical cancer risk factors and is an expert at the National Asian Women’s Health Organization, disagrees with Vu and other similar opinions.

Dr. Kuo said, “Personally, I think that Asian-American women do not get annual Pap smears because they just don’t see a gynecologist on a regular basis. I think this is more prevalent in the recent immigrants. I do not think racial stereotypes play into this, and I do not think that physicians see Asians as a group of patients who are less likely to get cervical cancer.”

“I can’t say that there is a misconception in the Asian-American community out there, but I think at least in the major city, the Asian-American community is fully aware of the importance of cervical cancer screening and the risk of cervical cancer related to these women.”

Furthermore, family values and tradition play a big role in spreading awareness about cervical cancer. Cultural misperceptions about Asian women are just one side of the story; the lack of education and awareness contributes to the growing number of Asian women who choose not to get cervical screenings.

Beatriz Villamor, a 27-year old Filipino media studies graduate student at the New School in New York, says that it’s not so much that the cervical screening tests and vaccines are not offered but that more Asian women are less educated about it.

“I’m not an Asian-American but a Filipino, and I find it really striking that even the Asian women who were born and raised in America have the same precautions and misunderstandings about cervical cancer, Villamor said. “90 percent of Filipinos are conservative Catholics, and families raise their daughters to be celibate, so people believe that cervical cancer, STDs and HIV/AIDS aren’t things Filipino women should worry about.”

Last year, Villamor said she decided to take the Gardasil vaccine because it would help save her from developing cervical cancer in the future. Gardasil is a cervical cancer vaccine that protects girls and women against four types of human papillomavirus (HPV). Gardasil’s official web site reports that the two types of the virus cause 70 percent of cervical cancer cases, and the other two types cause 90 percent of genital warts cases. Gardasil can be used by girls and women ages 9-26. Merck, a pharmaceutical company, first introduced Gardasil in late 2006 but was later approved for use in 2007. The vaccine is a process of three individual shots that can costs up to $360, which can be costly to some.

Moreover, there is not enough conclusive evidence that the vaccine works. Researchers and pharmacists are unable to prove how long immunity for the cancer will last, and whether the vaccine can lessen immunity to other strains of the virus. Although there is not enough corroborated evidence to support that the vaccines promise a healthier future for girls and young women, it is still a major breakthrough in the women’s medical health field.

Villamor said, “I figure, if you’re going to splurge on your summer vacation, then why not splurge to save your life. I think it’s extremely important that girls and young women protect themselves- sexually active or not. I also think it is ridiculous how people are afraid of the vaccine’s side effects. I mean, would you rather have cervical cancer than a small fever?”

Justine Bantilan, a 21-year old Filipino-American nursing student at Felician College in New Jersey, says that Asian women worry too much about what people will think of them, rather than standing up for themselves and think about what might happen if they did not take action.

Whether Asian-American women are just plain misinformed or not aware of the risks of cervical cancer, Bantilan says that their families and communities ought to know that cervical cancer does not discriminate against age, race, personality etc., and it can hurt anyone.

Bantilan said, “I believe that Asian-American women don’t get tested because they are afraid of the truth, but it’s time that they stop being in denial and protect themselves”.

Tiffany Ayuda is a freelance writer whose writing interests include, women’s health, Asian-American issues, eco-friendly living, family issues and New York culture. As a recent Hofstra University graduate with a degree in Print Journalism and minors in French and International Affairs, Tiffany would like to travel abroad and become an international news reporter in the future. 21 years young with so much to learn, her work has been published in The Chronicle, Pulse magazine, L.I. Pulse magazine, Nassau News, Collegenews.com, Elements magazine, gURL.com and The Hudson Reporter.

With the lack of Asian-American representation in the media, Tiffany was happy to have discovered ASIANCE Magazine. Tiffany is currently embracing her transition into the “real world,” a.k.a. finding full-time work and preparing for graduate studies in English Literature and Education.