Investing – Partial Solutions

Last month, when I last wrote, the outlook was rather pessimistic. The Dow had closed at a new multi-year low of 6,763.29. With little word from Washington, it was hard to know where things were headed. The bears had control of the market, and I argued that unless the Obama administration came out with action that addressed the banking problems, we would head steadily downward.

Since then, we’ve had the beginnings of a solution – partial solutions as I call them. We’ll discuss these steps, but all you need to do is look at the Dow at 7,716.18 as of market close on March 27, 2009, and the S&P at 815.94, to know that we’ve moved in a good direction. This month has also brought an interesting case study in trading and technical analysis that we’ll discuss in this article as well.

The Beginnings of a Solution

Let’s start with the partial solutions first. In contrast to the complete silence of February, Washington has emitted rumblings that indicate their position on several issues plaguing the market. First, on March 10, 2009, Barney Frank, Chairman of the House Financial Services Committee, indicated that he supported the re-instatement of the uptick rule. This rule would require a stock, once shorted, to move upward before it could be shorted again. In June 2007, the SEC voted 5-0 to eliminate this rule, claiming that tests proved there was no substantial difference in trading without it. The uptick rule had been in effect since 1938, and it was designed to prevent rampant shorting in market downturns.

The uptick rule is like a speed bump in a residential neighborhood. It forces everyone to slow down. My guess is that the SEC never tested the effect of the uptick rule under severe conditions – conditions like the ones we had in 2008. The other issue is that there are now many ways to short a stock. Options, futures, forward contracts and swap agreements can be used to create synthetic shorts. So the return of the uptick rule will help, although it’s not clear that it’s the complete solution.

Be that as it may, Barney Frank’s announcement that the uptick rule would likely be re-instated within the month helped spur a turn-around in the markets on March 10, and kicked off the current rally (or bear market rally, if you wish). That day, the Dow closed at 6,926, up almost 400 points from 6,547 on March 9.

The second major step was Geithner’s banking plan, announced Monday, March 23, 2009. The key component for many in Geithner’s plan was the public-private partnership to get rid of toxic assets on banks’ balance sheet. The markets have been frozen because banks and buyers have not been able to agree on a price. For example, the bank may want to sell an asset for 60 cents on the dollar, while buyers are offering 25-30 cents on the dollar. Geithner’s plan subsidizes the buyer by giving them cheap financing and taking a large part of potential losses. People are optimistic, because with government support, the buyer might offer 45 cents on the dollar, and the bank may consider selling for 45 cents on the dollar. It that’s the case, the toxic assets could be sold and taken off banks’ balance sheets. While there are still details to be worked out, and while it’s unclear whether banks and buyers can meet in the middle, there is at least a framework and a game plan for solving the banking problem. The plan was welcomed by the market, which soared on the news. The Dow closed at 7,775, up nearly 500 points from 7,278 the Friday before.

Lest we forget, Bernanke also gets lots of credit as well. In a sea of silence from Washington, he was the one voice in the administration with any substance, perspective and solutions. Back in late February, Bernanke testified that re-instatement of the uptick rule should be considered and that the government did not want to own the banks.

On March 10, 2009 – at the same time that Barney Frank was calling for re-instatement of the uptick rule – Bernanke testified before Congress and argued for “improvements” to the mark-to-market rule. He said that he favored changes, rather than suspension of the rule. Bernanke had long ago recognized the problems inherent in mark-to-market. In April 2008, Bernanke testified that “It’s also true in the current context, that mark-to-market accounting has been sometimes destabilizing in that sales of assets into very illiquid markets had led to reductions in prices, which have caused writedowns which have sometimes caused fire sales, and you get into an adverse dynamic which has caused problems in some of our markets.”

Bernanke gets kudos for giving investors – and the country – the sense that someone in Washington understood the problems and was acting to end the current crisis. Back in the midst of Geithner’s silence, Bernanke and the Fed was the only part of the administration that seemed to be doing anything. On March 18, the Federal Open Market Committee announced that the Fed was keeping the Fed Funds rate between 0 and ¼ percent; that it would continue to buy mortgage-backed securities; that it would continue to purchase agency debt; and that it would purchase up to $300 billion of longer-term Treasury securities (in the two- to ten-year range) over the next six months. In essence, the Fed was maintaining its commitment to being the buyer of last resort in an effort to get the credit markets moving.

Investors particularly liked the purchase of longer-term Treasuries. By buying Treasuries, the price of Treasuries would go up and their yield – or effective interest rate – would go down. Usually the Fed only buys short-term Treasuries, often a year or less in duration. That approach would move the short-term Treasury market, but not the intermediate- or longer-term markets. By buying two- to ten-year Treasuries, the Fed hopes to lower two- to ten-year interest rates. This in turn could get lending moving again and help unfreeze the credit markets.

Is It Enough?

You can pretty much guess my answer. No, it’s not quite enough.

There are still several issues to be faced. The first obvious problem is, will banks and buyers find a mutually agreeable price for these toxic assets? At the moment, investors are just happy that a roadmap has been identified. It’s not yet clear whether the process will work. I’m inclined to think that the private-public partnership can work, but no doubt the market will worry about the partnership not working.

And then there’s the much spoken-of-but-not-understood stress tests. It’s not really clear what the government wants to do with this. The Obama administration has said that it doesn’t want banks to fail, but there’s a lot of room for interpretation. I suspect that if they had their druthers, Geithner, and perhaps Bernanke, would want the power to take over and wind down, in an orderly way, any bank that failed the stress test. In fact, that may explain why the stress tests are taking so long – Geithner has already proclaimed his desire for sweeping regulatory powers that would allow him to take over failing institutions. If they are approved, then he could announce the results of the stress tests and then, take over and shut down the banks that failed the test.

The problem with this approach is that banks can still fail – that is, their stock can still go to zero, and that, in my mind, is the critical scenario. In other words, the current set of plans will still let an institution die, it just won’t be as messy and it’ll cost less than it did in the fall.

In my opinion, the better answer is to keep these institutions from failing, because it’s the losses for everyone that is associated with the institution that matters. And that means pulling back the bear raids and the forced fire sales of assets. The uptick rule would help slow the bear raid, but as I’ve mentioned above, that alone may not be enough. If it is, great; but if it’s not, mobilizing the political will to make further changes could take time.

Also, as argued in previous articles, the suspension of mark-to-market, or any adjustment that stops the forced fire sales created by mark-to-market, would be a big step toward saving these institutions. The Financial Accounting Standards Board is expected to vote on revisions to the mark-to-market rules on April 2, 2009. Any amelioration of the rule would help stop the bleeding in the banks.

In sum, we are talking about three major issues. First is the decline in asset prices, driven by delinquencies and foreclosures and accelerated through the banks via mark-to-market accounting. The second is the bear raid, which allows shorts to drive down the stock of major institutions that are troubled by “toxic assets”. And third, once an institution is in trouble, how do we wind it down without dumping a lot of taxpayer money into it. Between Geithner’s public-private plan and changes in FASB rules we may put a major dent in the first; Barney Frank may help take care of the second by re-instating the uptick rule; and Geithner’s expanded regulatory powers are meant to address the third.

At this point we have steps in the right direction. We don’t know if the plans will be executed, and we don’t know if they’ll be enough. It’s no surprise then, that the market is optimistic (evidence the recent rally), but is still, in a large part, in a wait-and-see mode.

One thing that’s particularly disappointing, especially from the point of view of an investor, is that Geithner does not seem to be particularly concerned about losses. He should be more focused on mark-to-market, short selling and transparency in the CDS market. If we can pull back the mechanisms that accelerate losses in the banks, and give the banks time to work out their problems, we could have a scenario where we make it out of this slowly but without a lot of losses.

The risk to investors is that Geithner would rather keep the system intact and worry about how to clean up the mess. Sunday night’s announcement that Rick Wagoner, CEO of General Motors, shows that the administration is not afraid to step in and run a company. This is effectively nationalization, regardless of whatever protests to the contrary Washington is making.

And here’s the problem with the government stepping in. A CEO will still be concerned about shareholders. The government will not be. And everyone will take losses in that case. Consider this scenario: Geithner announces the results of the stress tests. Using expanded powers he takes over the weakest banks and restructures them. The government forces the weaker banks to sell assets, and forces all stakeholders, stockholders and bondholders alike, to take losses. This is more like an orderly bankruptcy than anything else.

Think about it this way. If you have a mortgage that’s under water and you may have problems paying the mortgage, the bank can do one of two things. They could say, we’ll give you some forebearance on the mortgage, take your time, go work and slowly pay back your debt over an extended period of time. Or they could say, we’re going to step in, force you to clean up your act, sell your property, make you take your losses. Then we can all move on.

To me, it seems like Geithner favors the latter. And that’s the risk still inherent in the market. When the market was dropping in February, he said outright that he was more concerned about “bigger” issues. I still contend that the losses are the biggest issue. And believe me, there are harsher critics out there. George Soros, the famed trader who “broke the Bank of England” during the Asian currency crisis, recently said, “All we are doing right now with this talk of public-private partnerships and new regulation is ‘tinkering’. It assumes that the system is basically Ok. The idea that the markets are self-correcting has been proven false. The efficient markets hypothesis has been broken… Systemic risk is that markets are prone to create bubbles and we need to do something about that. I am very much in favor of short-selling. It actually deepens the market. However, I also recognize systemic risk. There are such things as bear raids, and they can change the fundamentals that markets can affect…”

So the risk to investors is that Washington will care more about “restructuring” than about losses.

Unfortunately, as investors, there’s not much we can do. We have hope, but much lies in the hands of Washington at the moment.

And Then There’s the Fundamentals…

So those are the issues on the regulatory side. Lest we forget, we still have the fundamentals to deal with. Next week, we start getting a bunch of news about the economy. As we get into April, companies start reporting their earnings. Now some say that expectations are so low, many companies will beat. Others say that average earnings for the S&P are still high. Commercial real estate and credit card defaults are still a problem, and should be in the earnings numbers in the next couple quarters. Couple that with mark-to-market changes that could create a major swing to the upside, stress tests that could swing the market either way and government action that could easily favor or hurt investors. In sum, you have a tremendously unpredictable month with major swings in both directions being possible.

So In the Short Term…

Some say the bottom is in. It’s very possible. I’m an optimist, so I like to think so. But if you’re putting your money where your mouth is, the question is, how sure are you? I don’t think you can be sure, so that means caution if you’re investing.

If you’re a trader, you could catch some of these movements. If you’re a longer-term investor, there’s no sure strategy. If you jump in now, there is downside risk. If you jump in later, you may miss out on some upside. So if you are a risk taker and can stomach some volatility, you can put money in the market or dollar average. If you’re risk adverse and want to be sure to preserve your capital, there’s nothing wrong with waiting until we have a green light, rather than moving when the lights are yellow.

The Longer Term Trends

Looking over the longer term, there’s some definite trends in our future. All of these are very tradable, or investable. Keep in mind, by long-term I mean 3-5 years at least. So there’s no need to invest today, and it’s probably best to play these trends when we approach a more stable market.

Treasuries will eventually decline.

Treasuries are considered a safe haven. Investors have flooded into Treasuries because it’s still considered one of the safest instruments around, driving up prices and cutting yields. And the Fed’s Treasury purchase program should add to that trend. At some point, as the economy stabilizes, the trend should reverse. Money will come out of Treasuries and into equities. Prices should fall, and yields will increase. A good way to play this trend is the TBT, which is a way of being short Treasuries.

The stock market indices will eventually rise.

It’s a matter of time. Today the Dow is at 7,800 or so. It’s very reasonable to think that the Dow will be at 10,000-11,000 within 3 years, and perhaps even back to 12,000 within 5-7 years. Same for the S&P. Today the S&P is at 817 or so. It could very well be 1100 or so in 3-5 years. So a 30% gain in that time is very possible. So buying a fund that follows these indices makes lots of sense. With the uncertainty in the next couple quarters, you could dollar cost average over the next six months.

Inflation will come.

It’s pretty certain that at some point, we’re going to have to deal with inflation. All these government programs, all this spending to save the economy and renew America, will all come at a cost. Right now, all that spending is helping to cut losses. But after the market stabilizes, we will have to pay for our spending. As inflation hits, gold, commodities, and TIPS (Treasury Inflation Protected Securities) will be good investments.

Buy the best-of-breed, surviving banks.

Make no mistake, the banks, especially the best of breed, will survive. And they will prosper. At the moment, that’s Goldman Sachs, Morgan Stanley and JP Morgan. Keep in mind that the key is the people and the leadership. If John Mack leaves Morgan Stanley, or Jamie Dimon leaves JP Morgan, you’d have to reassess this investment. Also, these banks have had a big run lately, so wait, as always, for a pullback. I own GS, MS and JPM.

Stable, cash-flow producing companies are always good.

There are still companies out there that strong, produce cash flow, and are not laden in debt or loaded up with toxic assets. Altria (MO) and Philip Morris International (PMI) remain two of my favorites. Both of these are tobacco, and I know that some people have an issue with that, but I feel obligated to at least offer it as an option. You can actually make investments in these companies now, or whenever there’s a pullback if there’s been a recent run. I own both MO and PMI.

Consumer staples will do well as the market returns.

I still like the P&Gs and the JNJs of the world. Don’t expect any fireworks here, these are slower, but stable companies. They have strong brands and will perform well as the economy recovers. One thing to note though. In the old days, people would say always buy these companies in a downturn. That’s no longer true. These companies have been hit by three factors: 1) the shift to private label brands in a severe downturn; 2) high input prices; and 3) currency translation problems when the dollar is high because a large percentage of their business is international. So they are no longer buys when we enter a market like today’s. But coming out, they can do very well. People will shift back to these brand names as their finances improve. These companies have also raised prices (or shrunk the quantity sold at a given price) while input costs have declined. So as the economy comes back, their margins should increase. And as we inflate, the dollar should fall, leading to better numbers internationally. I own P&G and JNJ.

Video downloading & delivery will be big.

Over the next 3-5 years, internet delivery of video content will explode. It’s already happening – you can see major games, events, television – all courtesy of the internet. Companies that assist in that delivery will benefit. One that I like is Akamai (AKAM), which speeds delivery of content. It’s had a big run recently, so wait for a pullback on this. I own AKAM.

Bookstores are dying.

Sadly – because I love ‘em – I have to say that bookstores are dying. Unless they change their formula, I don’t see how they can compete. If you want to buy a book, there are far cheaper sources (Amazon, the most well know) and many of them. Plus, as digital readers like the Kindle (and Apple is supposed to come out with a competing product) take hold of the market, companies such as Barnes & Nobles and Borders could be just like your local newspaper.

Credit card transactions will dominate.

It’s not new news that people are using credit cards more than ever. Especially in the digital age, credit cards are the payment method of choice. Companies such as Visa and Mastercard process the transactions – they don’t actually extend credit. So while they’ve been hit by a downturn in the economy, they won’t suffer the losses of a company such as American Express, which will face credit card losses. As the economy recovers and the number of transactions continue to increase, these players will just keep collecting fees for each transaction processed. Not a bad place to be. It’s hard to imagine these guys not doing well over the next three to five years. You can dollar cost average now or wait until more credit card losses hit the industry (and that’s because weakness in the overall economy will still be a negative for these stocks, even if they don’t have credit exposure).

A Little Technical Help

So we’ve had a nice little rally recently. As of Friday, March 27, 2009, the Dow was at 7,776.18. On March 9, 2009, the Dow was at 6,547.05. That’s an 18.8% rally in under three weeks. I caught some of it, which was nice. In my mind, the question is always, how can we catch it next time?

It turns out, the technicals can help. Now I will never claim to be a technical analyst, I much prefer the fundamentals. Still, technicals can be helpful, and the technicals combined with the fundamentals can be very powerful.

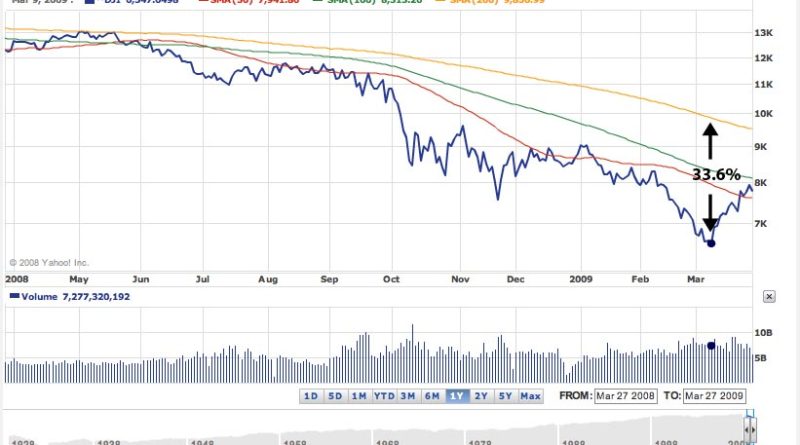

Let’s take a look at a chart of the last year or so. Within the harsh downward trend, you’ll see big dips, followed by significant rallies. In this chart, you’ll also see the 200-day moving average, marked in orange. On March 9th, the day before the recent rally began, the Dow was 33.6% below its 200-day moving average.

That by itself doesn’t mean much, but when you add that historically, it’s very rare for the Dow to be more than 30% under its 200-day moving average, we get a whole different picture.

The only other time that the Dow was more than 30% below it’s 200-day moving average was during the Depression. Rebounds usually follow such periods of extreme divergence. Some would simply call it reversion to the mean, which says, the further away that a path gets from its longer term trend, the more likely it is that the path will head back toward the longer term term trend. In other words, a rebound becomes increasingly likely as the divergence increases. And that’s the situation we had on March 9th – a high probability of a rebound when the Dow was 33.6% below it’s 200-day moving average.

Is this a category_ideline we can you for future trading? Let’s first look at recent history and see if it helps us.

| Date | Dow | 200 MDA | Precent Below 200 MDA | Follow Up Rally* | % Rally |

| 10/10/2008 | 8,541.19 | 11,991.11 | 28.8% | 9,387.61 | 9.9% |

| 10/27/2008 | 8,175.77 | 11,764.52 | 30.5% | 9,625.28 | 17.7% |

| 11/21/2008 | 8,046.42 | 11,418.07 | 29.5% | 9,244.59 | 14.9% |

| 3/9/2009 | 6,547.05 | 9,856.99 | 33.6% | 7,924.56 | 21.0% |

*For the rally following 3/9/09, represents the highest level through March 30, 2009.

So looking over the table, we’ve had four cases in the last year when the Dow was 30% or so off it’s 200-day moving average. In each one of those cases, a rally of 10-21% followed.

Interesting, yes? Of course, hindsight is 20-20, and the weaknesses are obvious. This technical indicator doesn’t tell us exactly when to buy, the size of the follow-up rallies vary, etc. Still, it does tell us that a bounce may be in the ballpark. Useful, I would say.

Until the next time, sleep well.

Ming Lo is an actor, director and investor. He has an A.B. from Harvard College, Cum Laude, and an MBA and an MA Political Science from Stanford University. Prior to going into entertainment, Ming worked at Goldman, Sachs & Co. in New York and at McKinsey & Co. in Los Angeles.

All material presented herein is believed to be accurate but we cannot attest to its accuracy. The writings above represent the opinions of the author, and all readers are urged to check with their investment counselors before making any investment decisions. Opinions expressed may change without prior notice. The author may or may not have investments in the stocks or sectors mentioned.